China 2008

Dreaming Canada, 3m, bronze, Changchun China

Artist’s Statement

December 18, 2007

I opened an email from the Arts Council of Windsor soliciting submissions for a sculpture competition in Changchun, China, on the themes of “friendship, peace and spring”. I had three days to submit a proposal and dropped everything to make it happen.

I submitted photographs and an artist statement for a 10-inch maquette in plastiline of a seated girl that I thought represented the themes of “friendship, peace and spring”. I had been working on it already and in haste named it Aurora Canadensis/Canadian Dawn.

The competition organizers responded that they were interested but asked to have the proposal fit more closely with notions of Canadian traditions and culture. Their aesthetic and sense of Canada had to be addressed and in addition they asked for a figurative work, something less abstract, even though the first proposal was very figurative in my mind.

I worked on new ideas, keeping within the boundaries of my own direction and integrity, and knowing that the Chinese committee was intrigued by Aurora canadensis. I wished to connect with the Chinese audience, make something that I would want to see myself, and also have it relate to a Canadian sensibility. A maquette emerged of an encounter between two figures, a beaver and a resting three-year-old child; it mixed some Canadian kitsch with the original proposal. The child/infant was resting under a “blanket” that was meant to submerge into the ground and grass. The head of the child appeared from under the blanket and the beaver sat looking at the child from the edge of the blanket. It was meant for presentation in bronze at a scale larger than human. As a friend commented: …it talks about peaceful co-habitation.

I submitted the new proposal under the title Dreaming Canada. In a world in which Chinese culture is ancient, the idea of a child or infant to represent Canada is not unusual, but in a China where ‘one child’ is a state legislated investment, a single child without a parent or mother transmits great emotional power and takes us away from usual Madonna/child or adult/child depictions. The beaver was included because of its many iconic and hackneyed qualities for Canadians but its extreme mystery for the Chinese because beavers do not exist on the Asian continent. Nor do the Chinese have any exposure to Canadian myths other than Gold Mountain and Dr. Bethune. I created an encounter between a child and a beaver that the Chinese might find perplexing and compelling and that I myself could focus as a harmonious encounter between humans, nature and cultural difference. We are a part of nature and not separate from it. We enjoy and value its mystery. The Chinese organizers liked my work and engaged me in an exceptional opportunity to make art. It felt like a dream to me to have such an invitation and I named the piece Dreaming Canada. It restores life and the relationships many Canadians wish for nature and culture.

On June 10, the Chinese committee accepted my proposal but wanted some understanding from me. What now? As they had been adjudicating proposals, a massive earthquake had hit Sichuan Province to become China’s first publicly acknowledged international disaster. In China and the world press, the worst of the disaster was focused on the thousands of school children who died in the ruins of poorly constructed state-run school buildings. A child lying down, as in my Dreaming Canada, evoked emotions much too intense for Chinese audiences and much too political for the authorities. The odd beaver became a strange looking mourner in the overall composition.

In light of the tragedy, I was asked if I could disconnect my work from their sorrow. I felt my work was being a bit compromised here, but I could see past the glare of political light. Continuing the dialogue was best. I informed the committee that I could agree to a new composition given the earthquake’s effects and they should feel confident about the new work. I wanted them to accept my word on the new composition without having to re-work the maquette first. At this point I was feeling very stressed. There was only a month to go before I was due in China to build the full-scale sculpture and I did not think I could make a satisfying work under such pressure. They agreed with me.

Dreaming Canada, 3m, bronze, Changchun China

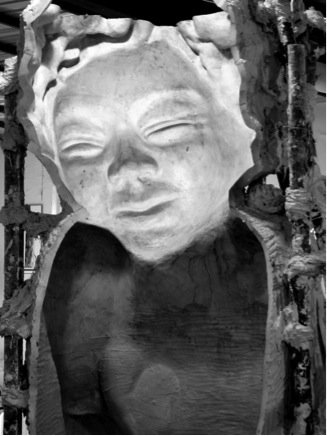

Negative of finished clay work

The competition was turning into more of a commission. I took up some more plastiline and commenced re-forming the Dreaming Canada maquette in an upright posture. I Flew into Beijing on the 20th of July with an almost finished maquette in my luggage. There I spent much of the first week trying to be an artist and not a tourist. The air was hot, polluted and unforgiving. In Beijing I finished the maquette just before leaving for Changchun on the 25th.

In Changchun about 50 sculptors from around the world had gathered to create their art to a completion deadline of September 10. I was the only Canadian and one of only 5 women among the crowd. In its imperial ways, China welcomed everyone with top down formality. Rows of waiting dignitaries, bouquets of flowers, curious onlookers, and bright red and gold big-character banners were commonplace. If a ceremony or a photo op could be imagined, it happened. And in my case there was a special twist in the events. Given my Japanese ancestry, my appearance was not foreign and it did not provoke the swarms of Chinese CCTV paparazzi and interviewers that besieged others. For the first two weeks, our hosts were convinced that my husband was the celebrity sculptor and that I was his Chinese interpreter. This misinterpretation was also assumed by most of the other sculptors for a short while. I received two types of treatment: either as an important international guest whilst wearing proper identification or as a Chinese person to be jostled without apology because I could not communicate. It was far too confusing for many Chinese that I, “ a Chinese looking” person, spoke English and needed a Chinese interpreter – perplexing but also inspiring as I was starting to see more deeply the layers of complication and meaning in my own work.

Once the introductory formalities were done, the 50 of us set to work on an imposed daily regime designed to complete our submissions:

Hotel Breakfast: 7:00-8:00

Shuttle bus to the studio work site

Work until 11:30 then shuttle back to the hotel for lunch

At 2pm return to the work site

Back to the hotel for dinner at 6:30

Work through most of the weekends and insert as much play and rest when we could. Some seemed never to sleep.

Building the full-scale work was an adventure. I was able to keep entirely to the conception and form of the maquette and create a 3 metre high version in clay that was meant to be remolded in fiberglass for national display in China on September the 5th and recast in bronze during this winter (2009) for permanent installation in front of the new People’s municipal building of Changchun. I had to complete the clay stage and leave the final steps of the fiberglass mould to skilled specialists.

On the 27th of July I was introduced to the site supervisors and formed my production team of four who would work with me to transform the maquettes into the 3 metre clay format. The assistants were university students at varying levels of study. The first was a computer programmer. The second assistant was a miracle in his second year of art school. He was intuitive and we were able to get to work right away as I found it easy to convey my intentions to him and work through the aesthetics easily although his sense of vision was very much classical Chinese.

My two interpreters were also invaluable and helped make the process manageable through a labyrinth of protocols and bureaucrats, many of who worked in deliberate opposition to each other. From the first encounter to my last day in Changchun they not only translated, but offered ways to see their culture, keep me sane, and understand bureaucrats and how China functions as layers of state authority. They were also so different, one privileged and connected to the authorities, the other driven from humble origins to make a successful business career. They proved superb at gaining concessions and advantages for me in the bureaucracies, the health system, and materials supply and giving me a very personal window into Chinese aspirations. We had a fabulous working relationship and the team formed a fast friendship.

Day 2

The day on the site was spent in a materials quest. Materials were a real surprise. None of the usual refined art supply stuff that you might expect in an operation that had been functioning for nine years seemed to exist. We had to improvise at every step. The clay was full of grit. Any scaffolding had to be built ad hoc from wooden scantlings. Worst of all, health and safety on the site seemed to be of no concern. Try working without respirators and goggles beside a fiberglass process or torches cutting brass and steel. Fortunately, we were eventually able to source some of our own safety items in a tools market and started slowly to educate our hosts and their workers. As well, the heat was oppressive under a tin roof and workers moving materials and visitors checking us out continually crisscrossed the close spaces of the work site.

Day 3

We started to build armatures, one for the beaver and one for the child, from curved steel rods and angle iron. The welding work was slow and getting the right depth to allow for the eventual clay work meant being careful. Scaling up was done by some simple math, measures and eyeballing. Some areas were filled out with wood. We wrapped the armatures in plastic sheeting and then wire mesh for twisting on small wooden cross-shaped supports this was all a surface built to hold clay. By August 7 we were about ready to put on clay and were also thinking hard about preventing possible slumps and slides, especially from the higher sections of the sculpture where most of the detailing was required. Some of the key solutions to avoid potential slumping were four-inch crosses made from finger-thickness wood and tied by wire to the armature and mesh in swarms at locations where gravity would bring down the clay. We had a much greater danger in the off centre leaning position of the head to the shoulder in the form. The possibilities that the weight of half a ton of clay and more would break the armature at the neck position and create our own Sichuan disaster was always with us. We were fortunate to sustain a balance, to create a strong foundation that not only supported the immense weight of the clay but it had to minimize yet absorb vibration. This was essential. We were very pleased not to have had any mistake.

Adding the layers of clay to the steel armatures started a very personal relationship with that primal medium. This work is done with the body and hands, with vigor, precision and as much physical force as one’s arms and cudgels can muster. Clay (roughly 8-10 inch cubes) supplied by labourers, was hauled out from a concrete pit and formed into soft bricks for use, and this clay was much recycled. We added clay to the armature in layers, punching and pounding out the air and driving the clay into the mesh and layers beneath. I made a conscious decision to move slowly and deliberately into this phase and we spent a long period observing other artists develop their techniques with these materials. The solutions seemed to be as numerous as the sculptors. I also had to pay close attention to the very complex weather of high heat, great diurnal temperature swings, and very variable humidity. Some days the clay would virtually dry in front of you and on others it stayed too wet. There was a constant evaluation of the moisture of the clay, too little meant crumbling and cracking and too much lead to unworkable muddiness. At the end of each day the work would be spritzed in water, supported where needed and then wrapped in plastic. The balance between too much spritzing of water and too little was very fine and changed as workdays proceeded. The condition of the clay at all times is critical as errors compound significantly and we attained obsessiveness in dealing with the medium.

The material has a wonderful personality that swings in tempo with the climatic conditions and even our own emotions. We had some rough days and I wished throughout that every day would be rainy and overcast because the clay behaved as I wished it to and I wasn’t roasting under the tin roof.

Going slowly in creating the armature and layering the clay proved to be the right strategy as in the third week other artists around me started to encounter clay failures and broken armatures. Mistakes cost some of them more than a week of repair work and some re-conceptualizing their pieces. In some cases, enormous stress among their teams caused very difficult human relations problems, compounded by cultural misunderstanding.

Day 29

Dreaming Canada is virtually done. The committee decided that assistants could be let go but did not tell the sculptors. I argued against this and appealed to the head artistic advisor that the young people were more than simply assistants. They were students in an internship that needed to be completed so they could see the process from start to finish. The next day my assistant was re-instated, this was an extremely emotional moment and statement for everyone not only on our team, but others congratulated me on the importance of my action.

The following days were all about details – time consuming and frustrating details about final textures, light refraction on surfaces, getting the hair so that rainwater would be shed away from the face and not stain the bronze, getting the beaver to just barely smile. I was trying to maintain a very clear vision now and keep out those around me who would say, “It looks like it is done! When will you finish? This period was an interesting time of fast work and mindful patience.

Photo shoot of the clay work – snap, snap, snap – documentation.

Day 33

All the clay work was done and the fiberglass processes began. Plasterers moved in very fast and traced moldable spaces across the expanse of the two pieces. Divisions were marked by lines of thin plastic cards pressed into the clay to separate the three dimensions of the sculpture into moldable units. Then the plastering was started. The first layer is like thickish cream, second layer like thick cake batter, third layer like very sticky bread dough. This is all slathered on by hand and the dripping loss falls over everything and everyone. Rough beams of young trees, tied together with coarse raffia dipped in more plaster hold the sections of the cast. The plasterers were fast and I had hoped the next morning to be able to make a few alterations in final details of the clay – nope, they worked during the night and the morning arrived with Dreaming Canada all plastered.

As soon as the plaster was set, the sculpture was taken apart, literally. It was very challenging to see the entire armature and clay torn apart and the shell of plaster/gypsum looking like a hollow phantom of the hard weeks of work that had past. I cried but not long because the fiberglass remolding started immediately. A sealant/release was brushed on the plaster mould. Squares of fiberglass were pressed and layered into the plaster molds with epoxy resin to a thickness of no more than 1 to 2 inches. It sets and then the plaster is shattered. A fiberglass positive remains. They are reassembled and sanded to remove any seams and provide continuous texture. Painters use aerosols and air brushes to layer on a faux patina finish; a black undercoat followed by successions of selected colour and highlights. A crane moves the fiberglass reproduction away to the city hall.

Day 41

The City of Changchun holds an opening ceremony and unveiling of the works. I fussed a bit with the final position of my own. It looked great, in a choice position at the city hall garden. Two arches of flowers and shrubbery frame the sculpture. I received a commemorative traditional scroll from the Mayor, and he congratulates me. A young boy drags his father over to see the beaver and climbs up on it. He then goes to touch the hand and look up at the face of the child. My interpreter says to me with a grin, ”You have reached your target”. My vision is blurred.

Epilogue

The participating artists were not present for the placement of the final bronze work. Though I had made clear and advance instructions to maintain the sculpture in the configuration you see in the image above, the sculpture was re-arranged. The sculpture’s face points toward the front of municipal building (with eyes still closed, mind you) and the beaver was placed as if it were feeding out of the child’s hand. I contacted the appropriate persons in charge, but I was given no indication the sculpture would be moved to conform to my original design. In this way, Dreaming Canada becomes a wholly different work.

I wish to thank and acknowledge, the City of Windsor, the City of Changchun, my team at Changchun — also, Karl Jirgens (for publishing this account in Rampike), Iain Baxter&, Noel Harding, Cecil Houston, friends and family.